Welcome to United Against Racism!

Fighting racism has always required courage. From its beginnings as a justification of the horrific global system of slavery, to its enforcement through lynchings, incarceration, and police brutality, racism is defended by violent and powerful systems.

The current attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and initiatives are just the latest form of resistance to racial justice. Opponents have mobilized to stop us from transforming our institutions just as the work has gained unprecedented strength.

The anti-DEI campaign is meant to intimidate and divide us. But with courage, we can remain united and undaunted.

That’s why this year, YW Boston’s United Against Racism campaign focuses on developing four types of courage especially needed to affect change in your organization and community.

You’re here because you know that racism is an evil that persists, and that united we can dismantle it and create a society where everyone has the resources they need to thrive, and where everyone can live with freedom and dignity.

You know that building more diverse and inclusive environments allows us to unlock everyone’s potential, enriching our lives and enhancing what we can achieve together.

You know that “DEI” isn’t a bad word.

You also know that others claim otherwise. Conservative activists have deliberately campaigned to drum up fear of antiracism—which is the practice of actively identifying and opposing racism with the goal of changing policies, behaviors, and beliefs that perpetuate racist ideas and actions—asserting falsely that increasing opportunity for everyone would reduce it for some. Some insist that being honest about America’s history and persistent challenges is “divisive.” Others have used mockery, intimidation, and even blatant white supremacist rhetoric to push back against the overwhelming calls for racial justice that reached new peaks in 2020, after George Floyd was murdered by a white Minneapolis police officer.

“It is understandable to feel fearful in the face of the inflammatory rhetoric being passed around in the media,” as YW Boston President & CEO Beth Chandler says. “Some may say that you need to be fearless, but that implies the absence of fear. Instead, I call on you to be courageous.”

Thank you for joining us in building our courage this year. With the four types of courage framed by educator Cathy Lassiter, Ed. D.—Empathetic, Intellectual, Moral, and Disciplined—we can remain united, and determined, to end racism.

FURTHER READING: Navigating DEI Challenges: Moving Forward in the Face of Resistance | YW Boston

2024 United Against Racism Curriculum

- About This Curriculum and the Participant Toolkit

- FAQs

- Lesson 1: Empathetic Courage

- Lesson 2: Intellectual Courage

- Lesson 3: Moral Courage

- Lesson 4: Disciplined Courage

About This Curriculum and Participant Toolkit

United Against Racism is an exclusive, self-paced curriculum designed to educate, contextualize, and empower organizations and individuals looking to better understand and address racism in Boston.

United Against Racism can be completed by individuals, or in guided group settings. We have included a supplementary participant toolkit to help organizations, groups, and individual participants practice self-reflection, engage in conversations, and plan to take action in support of racial equity.

Through the United Against Racism curriculum, participants will be able to:

1. Practice four types of courage in the context of their own DEI work

2. Apply these aspects of courage to defending DEI work in the face of opposition

The ultimate goal of DEI is to transform the systems and structures around us so that everyone can access the freedom and opportunities that enable them to reach their full potential.

This effort is collective—each of us has a role to play.

But since each of us brings unique life experiences, particularly with regard to our relationship with race and racism, we have to begin by building mutual trust and respect.

So, on the way toward building the courage to advocate for systemic change, we will spend time cultivating the practices of personal reflection and mutual listening. The Participant Toolkit is a supplementary PDF designed to help small groups of colleagues or community members engage with the ideas in this curriculum and apply them in real time.

The relationships you build through these challenging conversations are as important to the work as the ideas we present. We hope that all the skills you practice this month fuel your courage to remain united against racism—and sustain the pursuit of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the coming year.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will the United Against Racism curriculum content still be available after the campaign ends?

Yes! United Against Racism resources and content will be available to participants permanently.

Can I participate on my own and not as part of an organization or group?

Yes! Everyone is encouraged to participate. You can complete the curriculum on your own as well as with a group or as part of an organization.

Do I have to be based in Boston to participate?

No. The campaign is fully virtual and anyone can sign up to access our racial equity content.

Other questions?

If you have any questions about United Against Racism, please reach out to Aaron Halls at ahalls@ywboston.org.

LESSON 1

Empathetic Courage

| Objectives Participants will be able to: |

| – Define implicit bias and identify research-supported examples – Recognize microaggressions, and reduce the likelihood of committing them |

In order to secure and expand the work of antiracism in our organizations and communities, each of us needs to play a part in inspiring change. We will need to convince others to change their point of view and their behavior.

But disagreement and confrontation can be frightening, especially when other people hold tightly to their perspectives.

How can we gain the courage to navigate conversations about racism when we see it in such different ways? One way to begin is by understanding how our brains form judgments, and how those judgements can change. When we’re able to practice that change process mindfully, Dr. Lassiter calls this Empathetic Courage.

| EMPATHETIC COURAGE “Acknowledging personal bias and intentionally moving away from it in order to vicariously experience the trials and triumphs of others.” |

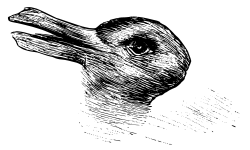

Let’s begin with a quick demonstration.

What do you see in the image above? Did you see a duck…or a rabbit?

Here is the image again:

Can you see both animals now?

It wasn’t hard to detect the first animal you saw. Our brains are designed to make rapid judgments with limited information. This usually serves us very well. But sometimes these judgements stick in place.

We form judgments like these constantly, from childhood—most of them useful, some of them damaging. When these associations are positive or negative value judgments, they’re called biases.

When we each consider our many identities, lived experiences, and the impact that systems of dominance and oppression (racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, etc.) have on us, we can begin to recognize the implicit (or unconscious) biases that we hold about others based on their identities.

| DEFINITION: Implicit Bias Implicit or unconscious biases are our tendencies to ascribe positive or negative qualities to a group, which can impact our judgments and decisions and lead to outcomes that are considered unfair. |

And just like with optical illusions, we can see beyond biases when we are provided with prompting or new information. Sometimes, though, it takes more cognitive work to do this than it took to form the initial conclusion.

This very simplified neuroscience sheds light on some important realities:

- Bias is human and universal.

- Bias is often unconscious, so we aren’t always aware when we exhibit it.

- With greater self-awareness, it is possible to mitigate the impact of bias.

It’s important to acknowledge that we can’t eliminate all of our biases—they are built in to how our brain works. However, we can develop a habit of recognizing them, and seeking out other perspectives to balance them out when they cause harm.

This very act takes Empathetic Courage.

Why does this matter?

Becoming Conscious of the Unconscious

Biases sometimes serve us well. But when we do not check them against reality—and especially when they become incorporated into systems used by whole groups of people—bias causes harm.

In every system, we can identify disparities that can be traced to implicit racial biases we develop throughout our lives. For example:

- Stanford researchers Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua found that teachers were more likely to label students troublemakers and judge their behavior harshly if they had stereotypically “Black sounding” names.

- Black patients are less likely to be prescribed pain treatment, possibly because many white medical professionals hold false beliefs about biological racial differences.

- Black male criminal offenders are given sentences that are 19.1% longer than white men for the same crimes.

While these biases make it harder for people of color to gain access to opportunities, other biases favor members of a dominant or majority group for opportunities, in ways that don’t necessarily reflect their appropriateness. These biases create or enable the accumulation of racial privilege:

- Affinity bias is the tendency to value people with similar interests or backgrounds to ours. If a hiring team comprises people who share certain identities, for example race, socioeconomic class, or college alma mater, that team is more likely to choose candidates who share their characteristics—even if other applicants are more qualified.

- Availability bias leads us to favor options we remember seeing or experiencing before. For example, an organization creating a parental leave policy might fail to include parents who choose to adopt a child.

- Association bias makes us assume that all the characteristics of one thing will also be true of another thing if they have something obvious in common. This helps us continue to advantage people who resemble those we are used to seeing with high status. For instance, a manager notices that a new hire does not have a college degree and assumes they’re less competent and successful than someone with a college degree and assigns them less challenging or important projects.

These universal habits help to explain why so many racial inequities persist, even among people who seek fairness and justice.

Identifying and countering the biases in the systems around us is a crucial part of building a more just society. We can hone our ability to do so by practicing on ourselves: when do our own biases show themselves?

The Impact of Bias

Our own biases show up in our interactions with people—though these biases are often only detectable by the people subject to the bias.

Because the same event can be experienced differently by two people, certain comments and behaviors affect people very differently depending on whether they are members of groups whose identities have been marginalized.

For example, complimenting a person for being “articulate” might feel very positive to someone who is white—but a Black person hearing the same comment might experience it as patronizing. Because the Black person may have repeatedly experienced that people often assume them to be uneducated or unprofessional, the “articulate” comment implies a sense of surprise and a negative racial bias toward Black people.

This is an example of a phenomenon called microaggressions.

| DEFINITION: Microaggressions The everyday, subtle, intentional – and often unintentional – interactions or behaviors that communicate bias toward historically marginalized groups. – Kevin Nadal |

There are countless examples of common interactions which are not intended to be insulting but are in fact demeaning from the perspective of the recipient. YW Boston has adapted a taxonomy of microaggressions, with explanations of the insulting message embedded in the behavior.

Even if you don’t understand why certain microaggressions have negatively impacted another person, empathy can help make clear why they cause greater damage than they might seem. Everyone has experienced being slighted or insulted. You might not share the same trigger, but you can remember how it feels.

People who hold marginalized identities often experience microaggressions throughout the day, every day. Microaggressions might look like being ignored on your way to work, patronized by a boss, interrupted by a colleague, and insulted by a friend—all because of your held identities. And in most cases, the person committing the microaggression doesn’t realize they had done so and will deny that they harmed you if you point it out.

Over time, these behaviors have a cumulative impact that can be measured on our bodies. Research suggests that rates of depression and other mental health issues are affected by microaggressions, and chronic stress and anxiety are in turn linked to heart failure, diabetes, and other determinants of health like willingness to go to the doctor.

Though you can’t anticipate every impact, you can reduce the microaggressions you commit by practicing these habits:

- Speak from your own experience. Catch yourself making generalizations or projecting opinions onto others because of who (you think) they are.

- Honor and respect the experience of others. When someone reacts differently to something than you would, don’t argue with them or advise them “not to get so upset.”

- Solicit feedback. Ask good friends whose identities are different from yours to tell you if they notice any biases in your comments or actions.

- Be accountable for your mistakes. Sometimes we only find out about a bias after we’ve acted on it—at someone’s expense. When that happens, own up, make amends if you can, and do better next time.

The good news is empathy isn’t all about suffering. Avoiding harm is crucial, but empathy opens us up to the joy, humor, and love of others alongside the pain. Forging bonds around the full humanity we all share is a life-changing byproduct of antiracism—and, in a way, its ultimate goal.

So, build habits and routines that expose you to people and ideas outside of your day-to-day routine: follow different voices on social media, use a different news source, listen to a different genre of music—or just invite a colleague or neighbor you don’t know for coffee.

With Empathetic Courage, we vicariously experience the trials and triumphs of others—helping us detect and move away from our biases. We also improve our ability to detect bias around us, whether in others (perhaps those who are critical of DEI) or in systems that affect our lives.

GO DEEPER: Look at page 4 of the Participant Toolkit for more reflection questions.

LESSON 2

Intellectual Courage

| Objectives Participants will be able to: |

| – Practice being open to new perspectives when receiving feedback about microaggressions – Explore the systems and processes where racism might be embedded in their communities or organizations |

Learning about other people’s experiences can be fun and fascinating, as we discover things about the world we didn’t know. It can also be challenging and frustrating because we have to update our own views with nuance where previously things may have seemed simple. Or we may have to accept that what we have considered to be true—and perhaps even acted on—might have been in error, and then engage in a process of unlearning and relearning.

Intellectual Courage focuses on looking inward: noticing and revising assumptions we hold.

| INTELLECTUAL COURAGE “Challenging old assumptions and understandings and acting on new learnings and insights gleaned from experience and/or…research.” “Paul and Elder [2010]…describe Intellectual Courage as being conscious of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs, or viewpoints which we once opposed or have not given serious consideration.” |

Let’s start with an exercise (credited to Tania Lewis, via Mark Collard).

- Using your index finger, point to an imaginary clock face on the ceiling (palm facing you) towards the 12 o’clock position.

- Move only your finger slowly in a clockwise direction around the clock face to form a large circle above your head.

- Continue to move your finger clockwise while slowly lowering your hand (and rotating in the same horizontal plane) below the height of your shoulders.

- Keep rotating your finger several more times.

- Now observe the direction of your movements. Is your finger still moving clockwise?

- Repeat the exercise three or more times to see if you can figure out why the direction of your rotating fingers changed.

As Mark Collard says, “Nothing changed about the way your fingers moved. The only thing that did change was your perspective.”

When Someone Tells You You’ve Committed a Microaggression

Suppose a person is offended by something you have said, and you don’t understand why. You meant no harm, and it was just a friendly comment. You may wonder, why are they making such a big deal?

When we step on someone’s toe and they shout in pain, we don’t hesitate to apologize. But sometimes when someone tells us we have done something racist or offensive, our first response is to defend ourselves and assert our own perspective.

One reason is that we tend see the world from our own perspective, and others see the world from theirs. As a result, our behavior impacts others in ways that differ from how we would be impacted. Their experience may be so different from yours that it seems to them you are moving counterclockwise when you are convinced you are moving clockwise.

On top of the cognitive dissonance we feel when faced with something that contradicts our expectations, we may also feel embarrassment or shame. Feedback is not always delivered the way we might prefer, so we may also find ourselves in a social interaction with emotional tension.

Calling on Intellectual Courage when we receive uncomfortable feedback allows us to take advantage of the opportunity to grow. Here are some tips to remember and reflect on, so that we can make feedback constructive even when it feels hard:

- Avoid defensiveness. Try to quiet the impulse to explain your own motivations and remember that your bias has had a negative impact on someone regardless of your intention.

- Actively listen. Someone has taken the time, and often a risk, to help you. Give them the respect of listening to understand what they have to offer you.

- Acknowledge and affirm. Say thank you for the feedback. Show that you understand the new perspective, even if you are still processing it, and apologize to the person or group who has been hurt. Learn what steps you might be able to take to repair the harm.

- Follow Up. Ask for additional resources or if you can continue the conversation, if appropriate. Communicate your learning to others to further counteract the bias.

Intellectual Courage may not be what we picture when we think of courage. But the curiosity, flexibility, and patience required to seek out and adapt to new information are demanding. It is easier to stay in our biases, but fighting racism means being brave enough to be humble.

If you have committed a microaggression and someone tells you so, you’ll have to challenge your old assumptions in order to accept the reality of their experience through Intellectual Courage. You’ll have to release the way you see the world, and take the leap that things appear different—but no less true—from another person’s point of view.

The same habits apply when we look critically at the systems, norms, and policies that we are used to. When we discover, or are informed of, an element of racial bias within them, we may need to use Intellectual Courage to overcome our own resistance.

New Perspectives on the World Around You

Injustices are not just interpersonal. Hurtful comments and biased behavior are only one manifestation of racism. In fact, more significant impact comes from racism that is harder to detect and take responsibility for.

This is systemic bias—the barriers to equity that persist in the underlying structures and assumptions of our organizations and communities. Practices, processes, and rules that cause resources to flow away from people of color and toward white people (and cause harm to flow toward people of color) might seem like “just the way things have always been.”

Because it can be harder to detect, racism at the institutional level can be incredibly damaging. So, while it is important to be attuned to the impact our own biases have on each other, we must never lose sight of the broader goal.

Uncovering where racism exists—and must be dismantled—in our workplaces, schools, volunteer organizations, civic institutions, or places of worship requires seeking out data that might not have been calculated or shared widely. Sometimes simply asking questions about racial disparities in hiring and promotions, student grades and suspensions, or homeownership and wealth can provoke strong negative reactions in ourselves and others. We all need Intellectual Courage to process the often painful information that will challenge our own narratives about the spaces where we exist.

GO DEEPER: Look at page 6 of the Participant Toolkit for more reflection questions.

LESSON 3

Moral Courage

| Objectives Participants will be able to: |

| – Compare the approaches of “calling in” and “calling out” – Classify issues according to the level of influence participants have over them |

Courageous people have been fighting against racism since it was brought to America to justify genocide and slavery, beginning with the brutality inflicted upon Indigenous peoples by European colonists. From self-liberating Africans and their descendants, to abolitionists who risked their reputations and lives, to the thousands of non-violent activists of the Civil Rights Movement, to the Native American activists who occupied their ancestral lands in defiance of Federal Government, the tradition of anti-racism is a part of our history—a rich tradition of American Moral Courage.

| MORAL COURAGE “Speaking up or acting when injustices occur, human rights are violated, or when persons are treated unfairly.” |

Watch these short videos to recall three moments of Moral Courage that changed the country:

Segregation and voter suppression may not look like they did in 1960s Alabama, but they persist today—and are defended by formidable power structures. Today those defenders often vehemently deny any connection to racism, while they put critics under enormous pressure to stay quiet, preserve the reputations of their institutions, and retain the status quo.

In the face of this opposition, we must summon Moral Courage to seek out, name, and prove that the larger forces of racism, classism, and other forms of oppression are at work—even in the organizations and institutions we are part of.

What does this courage look like for us today? What actions are we willing to take to name and oppose the wrongs we witness? What do we fear that holds us back? What skills will we need?

Speaking Your Values

Challenging systemic racism sometimes requires us to focus on the interpersonal level. When we need to confront, challenge, or persuade one another directly in order to prevent further harm, we call someone out to let them know that their words or actions are unacceptable.

How best to do this depends on the identities and relationships of the people involved. Those who are targets of micro- or macroaggressions may be in the most direct position to engage—but they also carry the extra emotional burden of being targeted. This adds two costs to responding. First, the intense emotion that fuels that person’s feedback may trigger defensiveness or even retaliation, making it less effective or safe. Second, summoning the energy to argue, explain, or educate someone on the harm they have done while you are still experiencing the harm itself takes a further toll.

On the other hand, the inverse is true for bystanders, especially those who belong to privileged groups. A white observer of a racial microaggression may hesitate to insert themselves because of social pressure to stay quiet—to not “rock the boat.” Yet, for the very reason that they were not directly attacked themselves, they may have access to more emotional resources. Ironically, due to pervasive bias associating whiteness with expertise, their feedback may even be seen as more “objective” or credible.

Because of this complexity, we should take our own identities and positionality into account when challenging people, particularly those with power, about something they have said or done. The guiding principle for someone on the receiving end of a racist interaction should be self-care. For one person, the courageous action might be to defend their dignity and call a person out, if that is what is necessary in the moment. In another situation, the braver choice might be to step out of the interaction into a restorative space.

Bystanders and white allies, on the other hand, should develop the courage to be more active. This may take the form of confrontation, when someone’s behavior is egregious and must be challenged decisively. But calling out isn’t the only way to do this. When we choose to call someone in, we invest in the relationship by providing context and knowledge rather than simply correcting and judging. This approach holds a person or institution accountable by elevating the values you both share and promoting the collective good, without diminishing or excluding the person for a mistake.

Calling in—speaking up with Moral Courage combined with Empathetic Courage—draws on practices like these:

- Be mindful: Call-ins should come from a place of caring: your intent is to help those around you grow and learn.

- Gain clarity: Ask questions to understand what the person said, as well as what they meant and what they were thinking and feeling when they said it.

- Reflection and explanation: Provide an explanation for what was harmful and why. Include additional resources when possible.

- Gratitude and grace: Thank the person for being willing to have a challenging conversation and remind them of how you value and appreciate them. We don’t throw people away.

We each have to choose the degree to which calling in or calling out suits a given moment. The deeper work is understanding what type of bravery calls you.

You Can’t Do It All

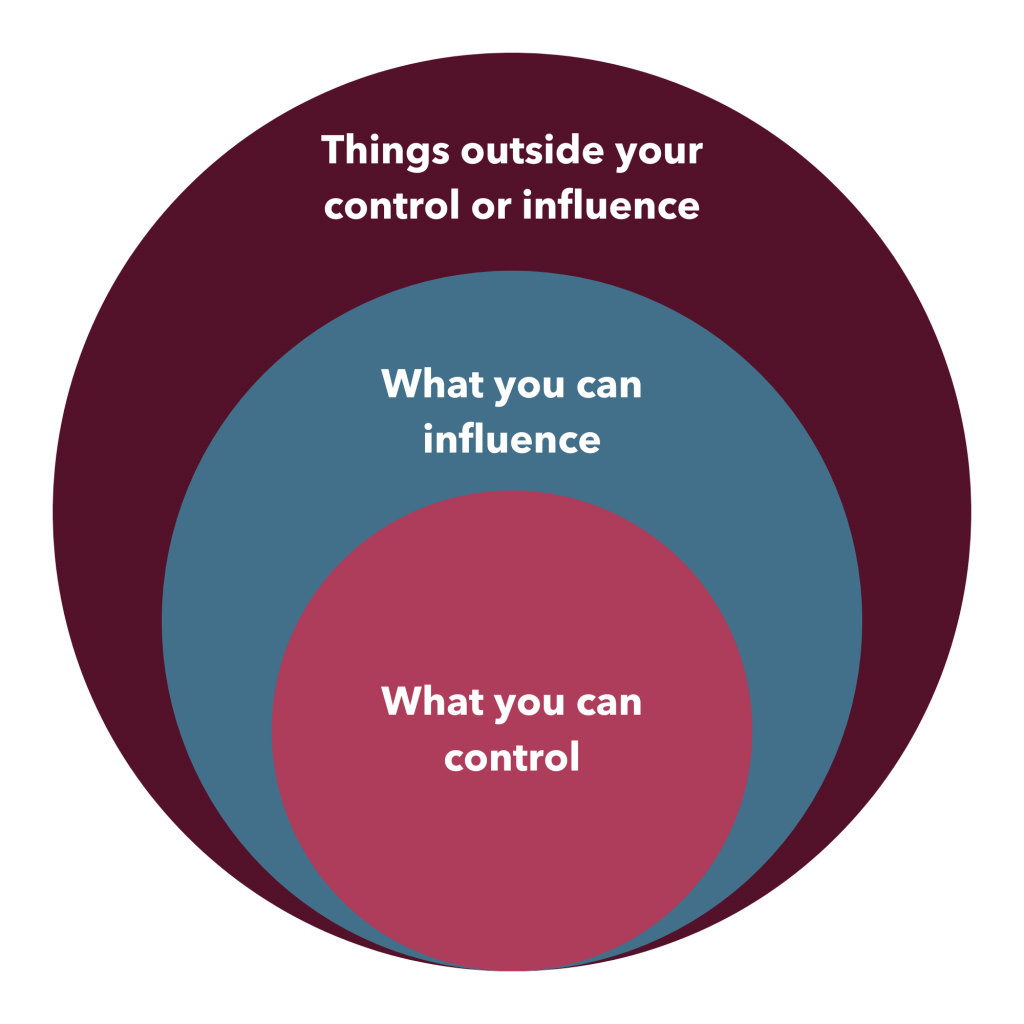

When we are tuned to the injustices around us, we may find ourselves overwhelmed with the amount of work there is to do. How do we maintain our courage to stand up when we know we can’t possibly affect every issue?

If you simply list all the possible ways an organization or community could improve, you might never reach the end. There is always more progress to be made. And in DEI, we feel the gap between the present-day insufficiency and the hoped-for state of equity especially painfully.

The reality of the scope of these problems may be so overwhelming that we feel completely disempowered. What can one person possibly do when the forces that create these injustices are so vast? Even if you hold a high-level position in a national or global institution, these are not dials on a dashboard that will change when you turn them.

That’s why one of the most frequently asked questions when people begin the DEI journey is “Where do I start?”

As Beth Chandler says, “For change to be successful, you need to keep the energy around change focused on the most impactful areas.” The more energy we put toward things we ultimately cannot control, the less capacity we have to work on what we can control.

However, if we spend time analyzing the specific spaces where our actions actually do affect others, we can focus our energies there and make impact that matters. We can choose to deploy our Moral Courage according to the sphere of influence that each of us operates in.

If you’re a leader in your community or organization, you may have direct control over policy or cultural norms. But even if you are a customer of a bank, a voter in your town, or a member of a club or congregation, you have some amount of influence and power to create change.

When we focus our work on these spaces of influence and control rather than those where we have little or none, we not only have a higher chance of successful change, we also grow our knowledge and experience. And our efforts often draw in others who want to be involved, or draw attention from other parts of the community. Thus, our circle of influence widens the more we work within it.

GO DEEPER: Look at page 8 of the Participant Toolkit for more reflection questions.

LESSON 4

Disciplined Courage

| Objectives Participants will be able to: |

| – Choose emotionally resonant tactics to counter resistance to equity – Analyze and reflect on the roles and strengths necessary to making change |

As conversations about and involvement in racial justice initiatives become more prevalent, opposition has risen—as it will to any social change that affects the distribution of power. The targeting of DEI programs specifically is a deliberate tactic of organized political actors, who are willing to present misinformation (as they did with critical race theory and any action they describe as “woke”) to achieve their aims.

However, in our day-to-day work in our organizations and communities, we are more likely to face resistance from people with sincere concerns. “Be ready to face various forms of opposition,” Beth Chandler urges. “The colleagues who say they value DEI, but then do nothing but slow or water down change processes, throw up roadblocks, and push back. A common example of small-picture opposition is saying ‘Oh, we live in New England; we don’t need to worry about racism/transphobia/etc. here.”

At times this resistance becomes frustrating and exhausting. It’s important to maintain our own health and equilibrium as much as possible. But if we are to overcome the backlash, we need to draw on Disciplined Courage.

| DISCIPLINED COURAGE “Remaining steadfast, strategic, and deliberate in the face of inevitable setbacks and failures for the greater good.” |

We need Disciplined Courage first and foremost to confidently defend the pursuit of equity that we know is essential. We need to draw on our own “why,” constantly reconnecting with the inner motivations that drive each of us. “To combat the distractions and opposition, make sure you have a clearly defined vision of success and check against it regularly,” as Beth Chandler says.

But we must also be thoughtful in our defense. Reacting to criticism of DEI with dismissal, condescension, or anger is not likely to bring anyone around to a new point of view.

Psychological Threats

Have you ever found yourself in an argument and found that the facts you present—well-tested evidence or your own experience—seem to have no effect on the other person’s understanding of the issue?

Just as we are all susceptible to forms of implicit bias because of our brains’ evolution, we are also subject to strong emotional responses that can override our cognitive clarity. Harvard Business School psychologists Eric Shuman, Eric Knowles, and Amit Goldenberg call these responses psychological threats: challenges to deeply felt values that are integral to our very identities.

When we experience a psychological threat, purely rational argument will likely not persuade us. Even when the data and facts are well known, the researchers suggest, some people will find themselves denying their validity, defending the status quo, or distancing themselves or the institution from them.

In the face of these emotional responses, though, the psychologists say we can employ psychological strategies that address the underlying anxieties that might be driving the resistance.

| If a DEI critic is experiencing a… | …these approaches may soften their resistance: |

| Status threat The fear that diversity initiatives are zero-sum: if members of minority groups make any gains, members of the majority group will necessarily incur losses. | – Draw attention to the “win-win” aspects of DEI initiatives (e.g., diversity can drive business growth and increase opportunities for everyone) – Frame DEI policies as working to value the perspectives and experiences of all groups, including the majority group |

| Merit threat The fear that recognizing the existence of bias, discrimination, and inequality “explains away” their own successes, implying that their achievements are due to their group membership rather than being earned. | – Before discussing DEI, invite people to reflect on a personally important trait, value, or achievement, why it is important to them, and how it is expressed in their life. This self-affirmation has been shown to make it easier for deniers to accept evidence of ongoing discrimination. |

| Moral threat The fear that acknowledging privilege tarnishes their moral image by linking them to an unfair system. | – Frame DEI initiatives as a way for people to express their existing moral ideals, not as an obligation that majority-group members must live up to. – Elevate examples of majority-group members who demonstrate their commitment to justice, to dispel the fear that they will be automatically associated with discrimination and privilege. |

Criticism of DEI has been coordinated and organized. But most people are guided by genuine values that support justice and fairness. Connecting those deeply held, positive visions to the actual work we are doing can bring resisters around to become allies.

And allies are key to making systemic change.

Just as we become overwhelmed if we target a change outside of our sphere of influence, we will burn out if we try to do every aspect of change-making ourselves. As Beth Chandler advises, “You don’t have to have a ‘must fix everything right now’ mindset—you must be able to see the big picture.”

That picture includes allies. And that means teamwork.

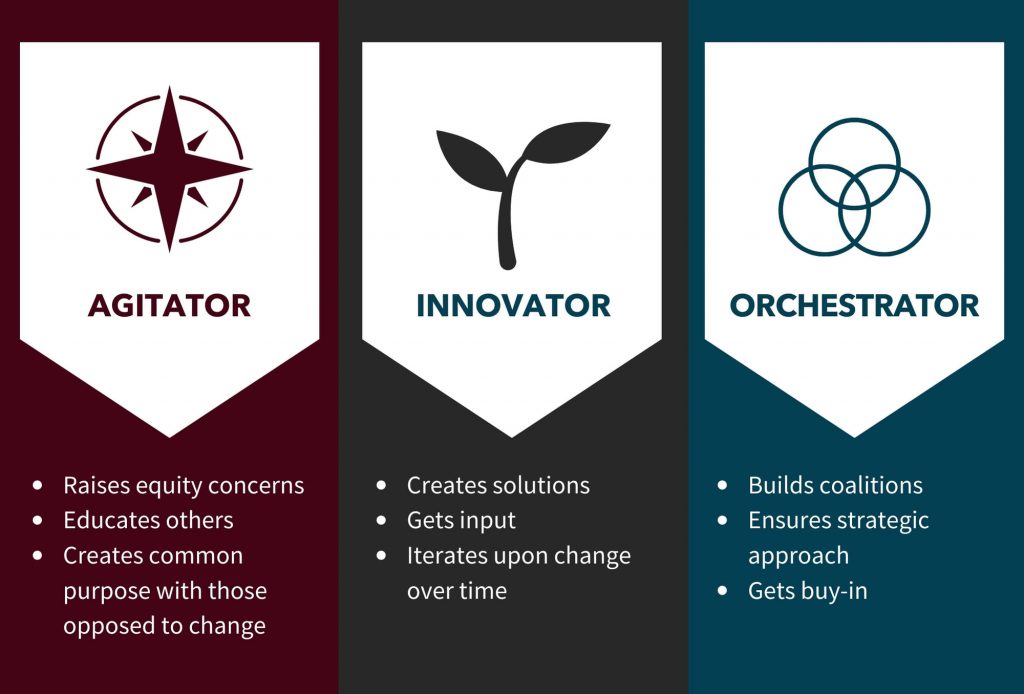

To truly advance social change, groups of people aligned around a goal must contribute individually, but in coordination. Organizing this way builds resilience—a kind of collective courage in the face of setbacks and failures. When some efforts stall or some people need a restorative pause, other people can maintain the momentum.

What types of contributions should you, individually, make? Many models exist to describe social change. Social scientists Julie Battilana & Marissa Kimsey (2017) identify three roles that work together to mobilize and move a group toward new practices:

What necessary actions are the best fit for your strengths, skills, and position, and what efforts do you need others to bring so that you can best achieve change together?

Developing our relationships with each other—enabling us to trust and respect each other across difference, even while helping one another to grow and learn—draws on our Empathetic, Intellectual, and Moral Courage. And those relationships are the foundation for collective action to make systemic change with deliberate, strategic, and Disciplined Courage.

GO DEEPER: Look at page 10 of the Participant Toolkit for more reflection questions.

Conclusion

Thank you for taking this journey with YW Boston.

We hope that reflecting on these four types of courage has inspired you. Hundreds of others in the Boston area are exploring these ideas together. Let their courage fuel yours. We aren’t alone.

Judge Nancy Gertner is a former U.S. federal judge who built her career around standing up for women’s rights, civil liberties, and justice for all. In a recent webinar with YWBoston, she calls on us to find a platform and use our voices to tell stories of why DEI matters to us:

You have to use your voice. That’s all we have.

Organizations need to tell the story of why diversity, equity, and inclusion is important to them, to remind their employees how it’s going to benefit everyone, what a diverse workforce brings to the table. People need to start telling the positive stories. And if we are leveraging all of the channels, they’ll eventually get out.

There’s a range of ways of making your voice heard. Obviously voting is one way. Demonstrating is another way. Letters to the editor, letters to your representative. Social media enables more voices than we had when I was growing up, and everyone should take advantage of that. People should run for office, run for school board. Think about all of the moments in your life when you interact with others. How do you use those moments? With your children? At the school board meeting?

You just have to keep on not shutting up. The worst thing is for us to remain silent in the face of what is really an assault. The unraveling of DEI is the unraveling of whatever progress we have made. We can’t fight that hard enough, because I think that the world we will leave for our children if we don’t speak out is so much worse than anything we could have imagined.

As we unite against racism for the rest of 2024, remember that this work is ongoing. In Beth Chandler’s words: “Change is not fast; it takes time and can be very slow and messy…Push through and keep momentum going over the long haul.”

And please share your experience with this curriculum in every forum. The more people see that the commitment to end racism endures all over Greater Boston, the more courage the community gains in the face of resistance.

We invite you to explore more resources and support from YW Boston. As the first YWCA in the nation, YW Boston has been at the forefront of advancing equity for over 150 years. Through our DEI Services—such as InclusionBoston and LeadBoston—as well as our advocacy work and F.Y.R.E. Initiative, we help individuals and organizations change policies, practices, attitudes, and behaviors with a goal of creating more inclusive environments where women, people of color, and especially women of color can succeed.

Congratulations, and best of luck.

Complete the Curriculum

To complete the United Against Racism and receive your official achievement badge, complete the form below.