February 19th: A Day That Should Live in Infamy

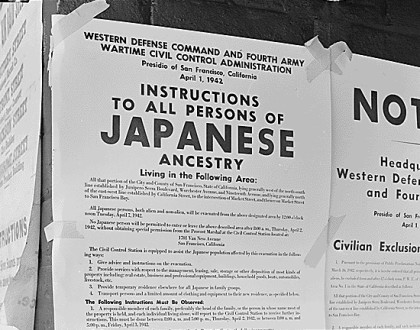

Much is taught about American national unification during World War II, yet a dark story of national division is often excluded from the narrative. 74 years ago today, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which called for the restriction and removal of residents in “military areas.” While this order was signed under the pretext of preventing espionage and protecting Americans, the discretion utilized under its enforcement was in flagrant violation of civil rights. Over 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were forced to leave their homes in California, Washington, and Oregon and relocated to one of 10 camps in desolate areas of the United States. Two thirds of those relocated were American citizens – like my grandparents.

Both US citizens by birth, they were forced to leave their homes in California. Heeding rumors that married couples would not be separated, they decided to marry immediately. Preparing for departure included storing what few precious valuables they owned in the basement of the Presbyterian Church that they had attended for years.

My grandfather burned his judogi for fear the martial arts uniform would raise suspicion of his allegiance to the United States. To the camps, they took only what they could carry.

“Relocated” people were gathered from their homes and sent to relocation sites before boarding trains with an unknown destination. Once arrived, the families departed from the trains and were greeted with barbed wire fences and armed guards supervising from watchtowers. Each family was given one room to share in the barracks, a communal mess hall served rationed food, and curfew was enforced nightly. They were not allowed to leave the camps without special permission and most lived behind barbed wire for the duration of the war.

Once relocated to the camp in Gila Arizona, my grandfather taught Japanese to American soldiers, and my grandmother continued to teach Sunday school. Despite facing such blatant prejudice, my grandparents were determined to prove their allegiance to the country they called their own. Upon leaving the camp in 1945, they returned with empty pockets to a ransacked church—none of their possessions remained.

“They didn’t talk about the camps much, it isn’t the Japanese way to discuss those things” my mother said about her parents. This silence certainly marked her upbringing. My mother never learned Japanese because her parents wanted her “to be American, to speak without an accent” – to be viewed as citizens of the country despite their racial lineage to an enemy nation.

This blatant violation of rights was viewed as permissible during wartime for matters of national security. Certainly fear of conspiracy and espionage was of great concern to the American government. So then, what became of Americans of Italian and German decent? If espionage and national security were truly concerns of the United States, it seems that the relocation of all persons affiliated with an enemy nation be distributed equally among these groups. Yet this was not the case. Only 300 Italians were interned and 5,000 Germans interned during the course of the war via Executive Order 9066 and similar restrictions, despite much greater populations residing in the country. The disproportionate targeting of persons of Japanese ancestry makes it clear that the implementation of the Order was driven by racism.

In 1980, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens concluded that,

“The promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity and the decisions which followed from it – detention, ending detention, and ending exclusion – were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

We look back on these events as confined to the past, and many people comfortably think, “This would never happen today,” but over 70 years later racial prejudice has yet to be resolved in this nation.

Now, in 2016, as the hapa descendent I’m still confronted with “where are you from?” despite my green eyes and wavy Jewish hair my father passed on to me.

I’m from California.

“But where are you really from?”

Questions like these make my blood boil, with clenched jaw I explain that I was born in California, my parents were born in the United States, and so were my grandparents. I’m an American. And the internment of Japanese Americans like my ancestors is only one example of how institutional racism has pervaded policy and unfairly targeted people – citizens – as wrongdoers.

In a time where people of color suffer from worse health outcomes and disproportionate rates of incarceration, a time where presidential candidates threaten to build a wall to prevent undesirables from creating a better life in this country, we must not make sweeping generalizations of groups of people.

Because unfortunately, the possibility of similar atrocities committed under the guise of “national interest” is far from imagined.

References:

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5154

http://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/

http://www.chicora.org/Japanese-Americans.html