March 31, 2020

Celebrate Suffrage by calling for more diverse representation in our government

This August, we will celebrate one hundred years since the Nineteenth Amendment was adopted in 1920 and women gained the right to vote in the United States. The 2020 Black History Month theme was “African Americans and the Vote” to honor those who fought for both of these Amendments as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This month, Women’s History Month, is similarly themed: “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote.” This year is an important one to examine the legacy of suffrage, including how voting rights have changed over time and how it has affected political representation today. As you likely know, the ratification of the 19th Amendment was not the end of the fight for suffrage, especially for voters of color. Because of this, we are still fighting for increased representation of women, people of color, and especially women of color in government. We can take this momentum to get out the vote this year and exercise our political voices to bring about equitable representation in government.

Americans have been fighting for the right to vote for centuries

Many people make the mistake of assuming the 19th amendment made it such that everyone could vote. However, many voters’ voices have been suppressed throughout the history of the United States, including today.

In the late 1700s, only white men aged 21 or older who owned land could vote. While the Fourteen Amendment of 1868 and the Fifteen Amendment of 1870 technically extended voting rights to all men in, many men of color, especially Black Americans and Native Americans were still denied the vote. Many states enacted formal poll taxes to literacy tests to limit the number of people of color who could access voting. Massachusetts introduced a grandfather clause in 1857 that enforced literacy tests for those whose grandfather’s could not have voted (thereby making it difficult for descendants of slaves and immigrants to vote). Voter intimidation was widespread, threatening violence to people of color seeking to vote.

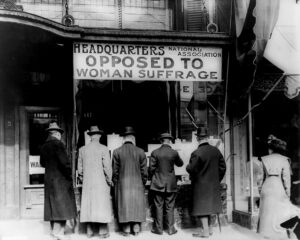

The women’s suffrage movement was a long and valiant one, but also did much to hurt and alienate black women. Before the Civil War, the women’s rights and abolitionist movements were closely aligned. The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the first ever women’s rights convention, featured Frederick Douglass as a major speaker. However, following the Civil War and the Fourteen and Fifteen Amendments, white women turned their backs on women of color. Their racism intensified, and they viewed advocating for black women’s right to vote as a liability to their cause. There were a number of black women suffragists who continued their fight for suffrage, such as Mary Church Terrell, who, at the 1898 National American Woman Suffrage Association convention, urged white women to recognize the overlapping discrimination black women faced. When the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, women of color were kept from voting by the same measures that had prevented men of color from voting for decades.

Following these amendments, organizers of color continued their work towards voting equality. Black Americans, particularly in the South, held voter registration drives, which peaked in 1964 with the “Freedom Summer”. The national attention from this movement encouraged President Johnson to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In response to continued work by Latinx, Asian American, and Native American communities, Gerald Ford amended the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to include language barring discrimination against ‘language minorities’.

Voter suppression remains today and it affects our representation

We have seen a great deal of progress towards voting rights, but voting is still inaccessible to many. Poll workers often utilize tactics such as scrutinizing people of colors’ IDs to discourage them from voting. Some states limit or disallow early and absentee voting, which harms people who, for instance, may not be able to take the day off from work. We cannot expect this challenge to go away with time. As the ACLU states, 30 states introduced voter suppression legislation in 2008, sixteen states of which passed said legislation. As those committed to racial equity, we have a duty to work to ensure all people can exercise full voting rights in the twenty-first century.

If we expand voting options, we will see an increase in voter turnout and an expansion of whose voice is heard in our government. Increasing voter turnout encourages candidates to examine and advocate for how their policies will impact the lives of people of color and women. We can only expect to see change in our government and policies when the electorate feels empowered to vote.

The suppression of people of color and women’s votes have led to the unequal representation of those voices in government today. Historically, women, people of color, and women of color have had a difficult time running for office. There is a long list of “firsts” for women, including women of color, holding public office. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the first person to run for U.S. Congress in 1866 and in 1887 Susanna Salter was elected as the first woman mayor. Despite these advancements, representation lagged. It was almost fifty years after the 19th Amendment was adopted that a black woman, Shirley Chisholm, was elected to U.S. Congress.

This lack of representation remains, even while we see women and people of color running for office at record-breaking rates. It is exceedingly difficult to be one of the few women or people of color holding or running for office. Women who run for office regularly report that voters and the media consistently ask them gendered questions, such as about their mothering or their appearance. Women of color, and Black women, in particular, find significant barriers when running for office. They face both sexist and racist assumptions about who can lead and are often expected to be superwomen who can ‘do it all’.

These barriers mentioned above are only a few examples of ways women and people of color are discouraged from running for public office, contributing to our lack of equitable representation. People of color and women make up approximately 40% and 51%, respectively, of the United States’ population. However, the US Congress only includes 22% people of color and 24% women. Massachusetts isn’t much better, with a 16% overrepresentation of white lawmakers and only 29% of women holding seats in the legislature. As of November 2019, “The House leadership team [in Massachusetts] is all white, while the Senate leadership has one Asian member representing the minority party. Of the 76 members who hold leadership posts or committee chairs, just four are people of color.” We have a long way to go to ensure equitable representation within our country’s and state’s government.

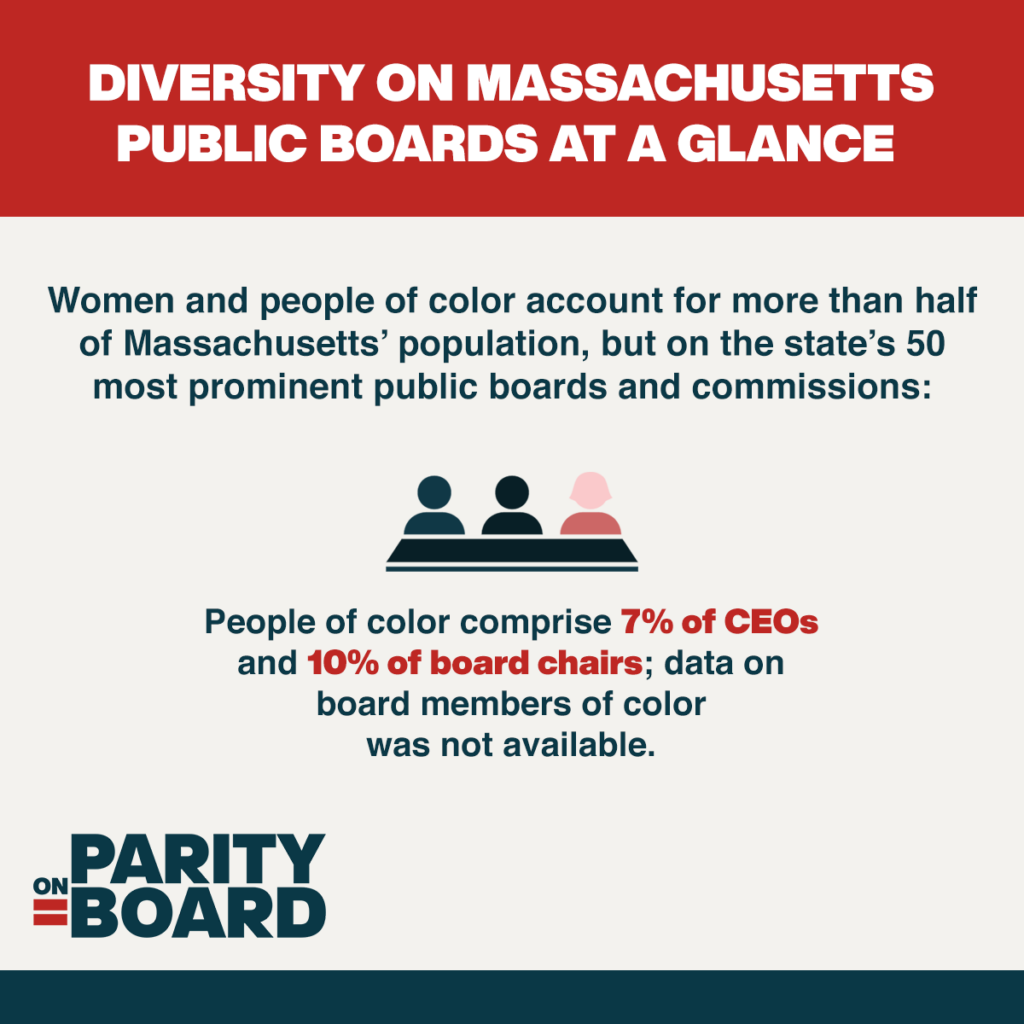

Support Parity on Board: Representation on our public boards and commissions

One area in which we can increase diverse representation in government is by appointing women and people of color to our public boards and commissions. A Women’s Power Gap Report published last year by The Eos Foundation found that in Massachusetts, women comprise only 39% of board members and 34% of board chairs on the state’s 50 most prominent public boards and commissions. The numbers become even more alarming when we look at women of color who make up only 6% of board chairs. Representation is even worse when you examine board chairs, only 10% of which are held by people of color in Massachusetts. This is a cause for concern given that women and people of color account for 51.5% and 28%, respectively, of the state’s population. We have an opportunity to increase gender and racial diversity on these boards and commissions, and by extension, our government.

Public boards and commissions are crucial because they allow citizens to be actively involved in their government and influence decisions that affect the quality of life of Massachusetts residents. Boards set standards and agendas for governing bodies, and commissions act as advisers to local and state legislative bodies. Running for office is just one way for citizens to become involved in their state government; our government also relies heavily on those appointed to public boards and commissions. Without representation of women, people of color, and women of color especially, our state will not have what it needs to make the best decisions for everyone in the Commonwealth.

YW Boston is leading the charge to achieve gender and racial parity on Massachusetts’ public boards and commissions. By passing An Act to Ensure Gender Parity and Racial and Ethnic Diversity on Public Boards and Commissions (H.4153), we can ensure that the composition of each appointed public board and commission broadly reflect the general public of the Commonwealth.

Join us and our Parity on Board Coalition. This movement honors the centuries of work toward voting rights and representation for women and people of color. There are two major ways you can get involved:

- Contact your State Representative and urge them to support H.4153 and to contact House Ways and Means Chairman Aaron Michlewitz, and House Speaker Robert DeLeo to ask for quick passage of this bill in the House of Representatives.

- Become a Parity on Board coalition member to receive updates on the status of the bill, have the opportunity to be a part of coalition meetings, and be the first to know of future interventions in support of this bill.

______

About YW Boston

As the first YWCA in the nation, YW Boston has been at the forefront of advancing equity for over 150 years. Through our DE&I services—InclusionBoston and LeadBoston—as well as our advocacy work and youth programming, we help individuals and organizations change policies, practices, attitudes, and behaviors with a goal of creating more inclusive environments where women, people of color, and especially women of color can succeed.